REFORMED DISTINCTIVES

___________________________________________________

The Reformation: the beginnings

On the 31st October 1517, an Augustinian monk, Martin Luther, nailed 95 theses to the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg, a flame that set alight what became the Reformation. He challenged the Roman Church to demonstrate eternal life can in anyway be earned by man. In 1524 he expounded the doctrine of justification by faith alone, sola fide, in his book The Bondage of the Will. It is a touchstone of Reformed theology. Not that this teaching was previously unknown, far from it, but it had just become submerged under growing mass of superstition prevalent at that time in the Church. Luther’s teaching conflicted with the selling of indulgences through the purchase of which personal sin could be forgiven. So apart from anything else, not only did Rome see its exclusive authority to forgive sins slipping away, but also should this doctrine spread there would be an adverse effect on its revenues.

As the Reformation spread, other Reformers such as John Calvin in Geneva also challenged the teachings of the Church. Another teaching that threatened the exclusive authority claimed by Rome was that of sola Scriptura. The Scriptures of the Old and New Testaments were the only sufficient and infallible guide to all matters of salvation and life. This set the Reformers on a collision course with the Roman Pontiff and the Church. The aim of the Reformers was to recover the purity of the Gospel and the Church of Christ.

The Council of Trent took place between 1545 and 1563, prompted by the Reformation it initiated the Counter-Reformation. Despite justification by faith alone having been taught in the Church previous to Luther all those teaching it were anathematised. Augustine of Hippo (354-430 AD) had taught it and Luther used his writings along with the Scriptures to defend it. The Reformation spread throughout Europe and was halted in its tracks only by the resurgence of the Catholic Church.

The Reformation in England

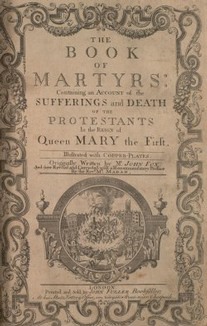

The origins of the Church of England grew partly out of Henry VIII’s (1491-1547) quarrel with the Pope, but not entirely so. He also crossed swords with Luther on repeated occasions. Henry remained a Catholic at heart until his death. The fight back against Reformation teaching took on the cruel form of the Spanish Inquisition which was copied throughout the Continent. The bloody purges of Henry’s daughter Mary I (1516-58) were a more than vigorous attempt to reverse the effects of the Reformation in England. Over 300 believers were burned at the stake, including bishops Hugh Latimer and Nicholas Ridley. Her persecutions were recorded in all their gruesome detail by John Foxe in his work The Actes and Monuments (1563). Better known as Foxe’s Book of Martyrs, it found its place in many Victorian households alongside the Bible. Whilst it experienced the influences of the Reformation, the English Church cannot to this day really be claimed as ever having been a solely Reformed Church. The nearest ever came to being such to such was during the time of the Puritans and the protectorship of Oliver Cromwell.

Calvinism and those of Reformed convictions were at their height in England at the time of the Puritans. Through charitable works, presence in government, scholarship and work in science and business Puritan influence far outstripped actual numbers. With the return of Charles II to the throne of England and the Restoration of the monarchy in 1660, this influence fell into irreversible decline. They were driven out of Oxford and Cambridge, removed from political office and the pulpits of the land.

The 1662 Act of Uniformity prescribed the prayers, sacraments and rites of the established Church of England as found in the Book of Common Prayer. It required episcopal ordination for all ministers, including deacons, priests and bishops. This had been previously abolished in the Civil War. Some parts of this Act were still in force until 2010. As a direct result 2000 clergy who refused to sign up to the required oath were deprived of their livings in what became known as the Great Ejection of 1662. This give rise to the idea in English society of what is known as ‘non-conformity’. A huge swathe of English society was thereby excluded from public affairs. Combined with the Test Act and the Corporation Act all non-conformists were excluded from civil or military office and from receiving degrees from the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge. Aimed at curtailing the activities of non-conformists, the Conventicle Act of 1664 forbade all religious gatherings of more than five people.

The effect of these draconian laws was to exclude Christian ministers and others from all public life. There were ministers, such as the renowned William Gurnall who did sign up to the 1662 Act. They thus were forced to confine their ministry to the personal spiritual life by implication denying the relationship between regeneration and the wider aspects of the Christian living in this world and society at large.

Further development of the Reformation

Since the days of the Reformation both the teachings of Martin Luther and John Calvin have been severely truncated and the writings of many others have been only selectively published. Too often Reformed theology has been reduced to the so-called ‘five points of Calvinism’, or TULIP: Total depravity, Unconditional election, Limited atonement, Irresistible grace and the Perseverance of the saints. Wiser heads such as the Princeton theologian, Benjamin Warfield (1851-1921), declined to confine Reformed doctrine in this way. Certainly, this formula is not without its value with regard to how God saves sinners, but it fails to include the wider aspects of Reformed thinking.

Outside the Lutheran tradition, which needs to be looked at separately, the theology that grew from the work of John Calvin has developed in two different directions. Early on in the Reformation, fiery preacher and theologian, John Knox (1514-1572 ), sought to reform the Church in Scotland. As a result he was forced into exile in Calvin’s Geneva. The doctrine of predestination lay at the heart of his teaching. On return his efforts in Scotland brought about the beginnings of Presbyterianism. For the Scots, the Westminster Confession of Faith became their doctrinal standard and they sought to translate its precepts into practical living.

Quite a different tradition developed in the Netherlands. Reformed doctrine arrived there in the 1560s. The Dutch Reformed Church was responsible for several important Reformed confessions. In 1561 came the Belgic Confession. Two years later the superb Heidelberg Catechism fostered unity between the Dutch and the German Reformed Churches. In the 19th century there arose a new group of theologians responsible for what is now recognized as the Dutch Reformed school of theology. Figures at the centre of this movement included Abraham Kuyper, who served for a time as the prime minister of the Netherlands. The distinguished theologians Herman Bavinck and Louis Berkhof also came from this school. Kuyper argued for the kingship and rule of Christ over every sphere of human life. Kuyper’s well-known words perfectly express his main concern: “There is not a square inch in the whole domain of our human existence over which Christ, who is Sovereign over all, does not cry, ‘Mine’” Kuyper saw in Scripture how God had established structures of authority within the different spheres of creation. It is not always appreciated that Kuyper was not the first to see these structures in the Word of God. They are found in embryonic form in the writings of the German Calvinist scholar, Johannes Althusius (1603-1654); some of whose complex Latin works have now been edited and translated into English. At around the same time, the English Puritan minister, Richard Baxter (1615-1691) was at work penning The Holy Commonwealth. Here too creation structures are found. Unsurprising, since all of these men drew heavily on Holy Scripture.

Boundaries between the different spheres secure order and justice within society. The sovereign rule of Christ is manifested as the revealed will of God is pursued in every area of life not just in activities connected with the Church. There are many points of similarity between the Dutch and the Scottish schools of theology. The most significant difference is that the Dutch believe that there is no such thing as religious neutrality in the human rational faculty. Consequently, common ground does not exist between believers and unbelievers. Rather than being an exchange of evidence, apologetics is instead a clash of worldviews. The present writer is inclined towards the insights of the Dutch School of theology rather than the Scottish.

The compromise with humanism

There was a flight from the cultural implications of the Christian and more specifically the Reformed faith, the protestant Church accepted little by little the dominant non-Christian humanist views of their day. The precious legacy of the Reformation was increasingly abandoned. From the Restoration period through to the latter part of the 18th century what happened was striking. Humanists such as the ‘father of liberalism’ John Locke had known the influence of Puritans such as John Owen at Oxford and were well acquainted with their teachings. Locke in turn influenced Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Voltaire, Immanuel Kant and many more. What then happened was that the humanists took what they knew of Christian teaching, removing all theological content from the doctrine and reproducing it as a secular world view. There are many examples of this. The biblical idea of a civil covenant so ably presented in what is thought to be a Huguenot work Vindiciae Contra Tyrannos (Defence against Tyrants) published around 1579, reappears in essence in a secularised version in Hobbes’ idea of a ‘social contract’ and Rousseau’s work of that same name. The sovereignty of God is transformed into the determinism of nature and the sovereignty of the human will. The priesthood of all believers and the introduction of voting of the laity in Church paved the way for the democratic model for politics. The Enlightenment view of the inevitability of human progress was a secular version of the triumph of the kingdom of Christ in history. Thomas Hobbes whittled down the definition of ‘will’ as the name we give a series of appetites, a mechanical by-product of sensation. His doctrine on the ‘Necessity of all Things’, which was essentially natural determinism that turned morality into an illusion, was a remarkable perversion of biblical predestination.

The unfortunate role of Jonathan Edwards

It is always difficult to be intensely critical of someone like Jonathan Edwards who is held in such high regard by so many. The good that so many find in him must not blind us to the many things about him that are highly questionable to say the least. There are several areas relevant to our discussion, all quite serious: First, Edwards espoused what amounts to a partial view of depravity. Second, following on from this, it is hardly surprising also that he held questionable views on the atonement. Third, a dissertation not printed in his lifetime that became available at the beginning of the twentieth century, shows him to have held a Sabaellien view of the Holy Trinity. Fourth, having placed the understanding of regenerate and unregenerate minds on the same neutral level, he then has little difficulty in calling on the support of unbelieving worldly philosophers such as John Locke to support many of his views. This was a first step in a sell-out to humanism.

It was central to Edward’s preaching that sinners all have a natural ability to repent. The natural man is merely morally corrupt and must face the consequences of his inherent moral depravity. His natural mental and physical faculties remain untouched by the fall. This is, of course, essentially the teaching of Aquinas and other Roman Catholic theologians. Edward’s dichotomous theory of ability and inability reflects a historic dualistic view of reality. It undermines a biblical defence of the faith as it supposes that shown the reasonableness of Christian teaching, the unbeliever can be persuaded to believe, whereas the truth is that without a complete change of heart wrought by the Spirit of God the natural man will continue to stumble around in the blindness in which he entered this world. As the Greeks, as Aristotle, as Aquinas, as Locke, as Edwards it seems, truths of the ‘natural order’ owe nothing to faith, but are discoverable without it. Calvin refuses to exempt any aspect of man from the effects of the fall. Once man sinned, his intellect, emotions and will are also fallen. None of these can therefore be used to deny sin or receive Christ. It follows that to ask a sinner to accept the Gospel on the basis of its reasonableness is to ask him to refuse it. Inability does not supersede responsibility, but rather makes the sinner’s continuance in unbelief certain and the turning of himself to true godliness impossible. Ability would imply a power which man does not possess to change his own condition. On the other hand, inability does not completely extinguish any of the powers which constituted man before the fall, but leaves them in a fallen state. The soul’s essence is not destroyed. Nevertheless, all faculties have a perpetual and total perversion to self-will and sin so that it is impossible for man of his own free will to repent of choose spiritual good for its own sake.

From Edward’s own writings (Miscellanies 710) we learn:

“’Tis entirely in man’s power to submit to Jesus Christ as Saviour if he will, but the thing is, it never will be he should will it, except God works it in him.”

We need to look at the first part of this statement that it lies within man’s power to submit to Christ. This is not the teaching of Scripture, but strikingly similar to that of Catholicism where the rational and voluntary nature of man, the will, is thought of as still being intact. The natural man has no need of the light of Scripture or illumination of the Holy Spirit to understand the world or himself aright. On the other hand, the fallen moral corruption needs added supernatural or spiritual renewal to incline the heart towards God and correct the ‘disturbance’ caused by the fall. Yet, in reality the natural man is destitute of the life of God, of spiritual life. In his entirety, he needs to be renewed by the power of the Holy Spirit. It is in the heart where man thinks, feels, will and then acts. The sinner needs a new heart, a new self, a whole change of character in every part to become a new man, to “put on the new man, which is renewed in knowledge after the image of him that created him” (Colossians 3:10).

Edwards continues “…Men are under no such inability to any moral good required of them as is owing to any defect in the capacity of their nature. …No man is condemned properly because he is unable, but because he is unwilling.”

However, the Bible itself says something different. In our natural state, we cannot fulfil the laws demands, cannot please God.

“…the carnal mind is enmity against God: for it is not subject to the law of God, neither indeed can be. So then they that are in the flesh cannot please God.” (Romans 8:7-8)

Furthermore, we are already born condemned so that the question of ability or inability hardly arises. Judgement and condemnation come upon us already not because of that we can or cannot do, have or have not done, but because of what we are, born sinners.

“Therefore as by the offence of one judgment came upon all men to condemnation; even so by the righteousness of one the free gift came upon all men unto justification of life. For as by one man's disobedience many were made sinners, so by the obedience of one shall many be made righteous.” (Romans 5:18-19)

His teaching is all so very different from the Reformation text by Martin Luther, Bondage of the Will, the title itself is strikingly different from Edwards’ Freedom of the Will. In his book Luther challenges the definition of ‘freewill’ given by Erasmus as “a power of the human will by which a man may apply himself to those things that lead to eternal salvation or turn away from the same”. Luther disproves this definition of the human will, asserting that everyone is under the wrath of God and only does what merits wrath and punishment. Man wills nothing but evil and is the slave of sin. “Where now,” says Luther, “is the power of free-will to endeavour after some good?” Calvin viewed every aspect of human nature as ‘necessarily wicked’. This concept is echoed by Abraham Kuyper: “All the utterances of a dead soul are sinful, even as the dead body emits only offensive odours.”

No one can bring a clean thing from and unclean one. “Who can bring a clean thing out of an unclean?” Job asks, “not one.” (Job 14:4) Sin saturates the whole of the individual being, pollution darkens the understanding inclines the will to evil and makes it powerless to make a move towards saving good. “Because the carnal mind is enmity against God: for it is not subject to the law of God, neither indeed can be.” (Romans 8:7) “Unto the pure all things are pure: but unto them that are defiled and unbelieving is nothing pure; but even their mind and conscience is defiled.” (Titus 1:15) The body and all its members are a weapon of unrighteousness. All men have already died in Adam. Our Heidelberg Catechism makes clear the Reformed position that man is inclined wholly to evil and is incapable of any saving good.

Scripture teaches that man is both guilty and responsible and that he is obliged to turn to Christ, but that he cannot even will to do so. His inability is total and will remain so unless God in mercy touches his soul. Every ounce of man’s being vitiated by wickedness, he is consequently incapable of even perceiving the things of God. He cannot and he will not, but he still remains a responsible agent and accountable to meet the righteous demands of a thrice holy God. All men are corrupt in the totality of their being: mind, intellect, emotions, will conscience and body. Such depravity leaves all men unable to make any move towards Christ without first God gives them a new heart.

The Presbyterian preacher and father of American evangelism, Charles G. Finney (1792-1875), although he disputed many of Edward’s views, he was nevertheless a great admirer and sought to emulate him. An examination of Finney’s writings in particular his Systematic Theology reveals that he was able to build on the foundation laid by Edwards and take matters a step further. Seeing that Edwards taught that it was ‘entirely in man’s power to submit to Jesus Christ’, it was only then a short step to Finney’s Pelagianism. Twentieth century evangelistic practices and decisionist calls to trust Christ run in a straight line back to Finney but also a step further back to Edwards.

Edward’s private notebooks and Miscellanies show that he abandoned the reformed doctrine of the imputation of Adam’s sin as the ground of natural depravity. Equally serious, he undercut the connection with respect to imputed righteousness between Christ and the elect. A theological movement, the ‘New Divinity’, was developed by followers of Jonathan Edwards. They held to what is known as the ‘Governmental Theory of the Atonement’ which denies that our salvation is based on the expiatory suffering of Jesus Christ on the cross. Whilst Edward’s published works reveal no open promotion of such views, some of his sermons, especially those before 1733, show him using vocabulary that point towards the New Divinity doctrine. It is clear that Edwards would have been teaching these doctrines to his eager students.

A further very serious departure from sound doctrine was revealed in an extraordinary dissertation on the Trinity. It was not published, but eventually came to light early in the 20th century and was verified as genuine by Benjamin Warfield. Rumors of its existence had circulated for many years. Edwards sent it quietly to some ministerial colleagues for their review. Some exclaimed in horror that Edward’s views of the Trinity were Sabaellian. This view states there is only one person in the Trinity and that the three ‘persons’ are but different aspects of that one person. Edwards was attempting to construct a rational proof for the existence of the Trinity. He states that God created a mental image of Himself and this is the second person of the Trinity. God loved this image of Himself so much that the bond and force of this love between God and this image became so overpowering that it became the third person of the Trinity, the Holy Spirit. The precious Son of God our Saviour is reduced to a mere mental image of the Father and the Holy Spirit, the divine self-love to a divine attribute.

At the time of Jonathan Edwards (1703-1758), Hobbes’ books were reaching the New World and having a huge impact. Rather than reaching for an answer that was grounded in the Word of God, Edwards turned to John Locke whose works he had devoured even as a boy: humanism and philosophical speculation to answer Hobbes’ godless doctrine. Edward’s On the Freedom of the Will contains few biblical texts or allusions, but numerous quotations from Locke. Many of Edwards’ addresses were in fact clothed in the garments of Lockean philosophical speculation or Newtonian scientific theory of which his hearers would as likely as not have been completely unaware. According to an early biographer, Samuel Hopkins, among very few who knew Edwards intimately, he confessed to friends in later life that already at the age of fourteen, he derived more pleasure than “the most greedy Miser in gathering up handfuls of silver and gold from some newly discovered treasure” from reading John Locke. The warning of the apostle Paul to the Colossians is apposite. “Beware lest any man spoil you through philosophy and vain deceit, after the tradition of men, after the rudiments of the world, and not after Christ.” (Colossians 2:8)

Edwards did not follow Locke in all points and there were many other influences upon his thinking, including Cambridge Platonists such as John Norris, but also by George Berkeley and Isaac Newton, as well as by the French Oratorian priest and rationalist philosopher, Nicolas Malebranche. His philosophy and theology raise many questions as to the nature of the so-called ‘Great Awakening’ (1734-35). European rationalism was making huge inroads in New England at the time, yet Edwards having compromised was in no position to fight the apostate patterns of thought all around him. The spirit of apostate synthesis made him impotent in any attempt to hold back the tide of Enlightenment theory that had taken hold of the founders of the American Federal Government. Rather than seek to recover biblical ground, this was to be the way forward.

Secularised humanist doctrines were re-imported from many different sources, but this was done without any attempt being made to re-establish the original biblical foundations. Natural law theory and Unitarian humanism among other influences established autonomous reason at the heart of theology and the ‘Christian’ view of science and the world. Once it became evident that they would have to choose between humanism and the Bible in the wider spheres of life, those wanting to keep the Scriptures narrowed their definition of the faith exclusively to theological principles, particularly those concerned with personal salvation. The Christian faith thus shrank in its influence until the legacy of the Reformation practically disappeared from view. Few evangelical Churches these days teach six-day creation as being science or the early chapters of Genesis as being history. The watchword is: ‘The Bible is not a book of science or history.’ When called upon publicly to defend the marriage of one man to one woman, they are often at a loss, grasping for humanist and secular arguments instead of insisting that the institution of marriage is a creation ordinance put in place by God historically in the Garden of Eden.

Humanism is the post-Christian religion of western nations. An accommodation has been reached between the Christian faith and the humanist religion, for that is what it is. The human will, individual or collective, is the final source of ‘values’ by which all individuals and societies have to live. The public realm in all its spheres is autonomous, secular. Revealed religion is excluded and confined to the privacy of the home and the Church. Even here it is no longer safe from attack. The Reformation principle that the Scriptures are a guide not just for the home and the Church but also culture and society has been jettisoned even by those professing to be followers of Christ. The choice is between a way of life for all men that is directed by Scripture or a synthesis between the Truth of God’s Word and the blatant godless lie of apostasy. Christians and non-Christians are said to be able to perform their tasks equally on the basis of human reason which has not been negatively affected by the fall of man into sin. This is the lie. The triumph of the Gospel and the return of Christ, the true King of kings, has been replaced by the progressive realization of an earthly paradise.

Reformed distinctives

The reformed faith is far wider than the narrow confines of individual salvation and matters concerning the soul. Certainly, it is that, but also very much more. Portraying reformed belief in this way makes it far too narrow and fails to apply the faith to the whole of our living day by day. It overlooks the fact that the whole of God’s creation still belongs to Him and that in every sphere of life we ought to live to His glory. Confine our faith to salvation and in all other things we can operate like anyone else. This way of looking at things is neither biblical nor reformed. Our faith reaches to all areas of life for all, believer or non-believer. There is one God and it is to Him that all men owe homage and obedience. This affects our views of the family, marriage, abortion, education of our children. It affects the way we pursue all our daily work. Incorporated will be our view of science, seeing our world and all in it as created by God and belonging to Him.

In the introduction to his book Reformation or Revolution (New Jersey, 1970, p.1), E. L. Hebden Taylor draws attention to a character in A. A. Milne’s book Two People (London, 1947)

“Mr Pump was not a hypocrite. He was a religious man, whose religion was too sacred a thing to be carried into his business. The top hat that he hung up in his office was not the top hat that he prayed into before placing it thus hallowed, between his feet, even if the frock coat and the aspect of benevolence were the same. He had two top hats, and one hat box for them. On the Monday morning he put God reverently away for the week and took out Mammon. On the Sunday morning he came back – gratefully or hopefully, according to the business done – to God. ‘After all,’ he said, ‘No man can serve two masters at one and the same time.’”

There are many Christians today who think very much along the lines of Mr Pump. One or two hours a week you will find them in Church, but for the rest of the week when pursuing their profession or trade they hardly have any sense of relating their calling as Christians to pursue the glory of God in what they do. It would seem they have little to offer men and women around them. The Gospel appears as irrelevant to the way life has to be lived in the world of today. Without the conviction that being a Christian makes a recognisable difference in the way we do our work and live our lives, no one can be expected to see that the sovereign saving grace of God has any significant meaning for their earthly lives.

In this compromised view of the world, nature is largely self-sufficient: plants, animals, and human beings. Everything works well and is free from the influence of the fall and is not in need of redemption. In the fall, it was only the relationship with God that was disrupted; natural things including human reason continue to exist normally. Grace operated in addition to the natural, perfecting it. The biblical reformed vision is quite different. Everything created has been affected by sin and is in need of redemption. Sin pervades everything including every relationship within which we operate. It is the cause of all hatred. The power of sin and evil is not equal to that of God’s Word. It can disrupt but not destroy nature. Redemption restores the whole of creation to the place where God’s glory shines forth unhindered.

“And, having made peace through the blood of his cross, by him to reconcile all things unto himself; by him, I say, whether they be things in earth, or things in heaven.” (Colossians 1:20)

“Blessing, and honour, and glory, and power, be unto him that sitteth upon the throne, and unto the Lamb for ever and ever.” (Revelation 5:13)

The reformed confession rejects the nature-grace dualism present in Roman Catholic theology, and much protestant theology. The reformed Christian recognizes the wide ramifications of this in daily life. Whatever profession pursued, he or she will take the presence of sin seriously in every sphere of life. All of creation must be interpreted in the light of the Holy Scriptures.

“For ever, O LORD, thy word is settled in heaven. Thy faithfulness is unto all generations: thou hast established the earth, and it abideth. They continue this day according to thine ordinances: for all are thy servants.” (Psalm 119:89-91)

The reformed Christian is realistic about the impact of sin on the human mind whether in matters spiritual or natural. We can give no place to anything approaching the autonomy of the human mind nor seek alliances with non-Christian philosophies in the interpretation of the Bible. We will always be mindful of the warning of the apostle Paul:

“And be not conformed to this world: but be ye transformed by the renewing of your mind, that ye may prove what is that good, and acceptable, and perfect, will of God.” (Romans 12:2)

Faith is always totalitarian in its demands and eventually at some point one faith will destroy the other.

We glorify God and worship Him not only in Church on a Sunday, but every day in all that we do. Our mentality is not that of poor Mr Pump. A secular society assails the Church and seeks systematically to dismantle every remnant of the Christian faith for which Christians themselves seem to be losing out in every sphere. The problem arises because few are prepared to live out the power of their faith in real life situations. The power of the reformed faith does not lie alone in our confession but that faith in action. It is more than a system of theology or confessional statements; it is a whole way of life. It determines the way we interpret life and the world.

A biblical reformed Christian believer has made a deliberate decision to think and live according to the conviction that the whole world and life belong to God. It derives its power from God’s own acts in the world right now. A good summary of this understanding of salvation can be found in Paul’s epistle to the Colossians 1:12-20.

“Giving thanks unto the Father, which hath made us meet to be partakers of the inheritance of the saints in light: Who hath delivered us from the power of darkness, and hath translated us into the kingdom of his dear Son: In whom we have redemption through his blood, even the forgiveness of sins: Who is the image of the invisible God, the firstborn of every creature: For by him were all things created, that are in heaven, and that are in earth, visible and invisible, whether they be thrones, or dominions, or principalities, or powers: all things were created by him, and for him: And he is before all things, and by him all things consist. And he is the head of the body, the church: who is the beginning, the firstborn from the dead; that in all things he might have the preeminence. For it pleased the Father that in him should all fulness dwell; And, having made peace through the blood of his cross, by him to reconcile all things unto himself; by him, I say, whether they be things in earth, or things in heaven.”

The Creator of the world came into the world He had made to save it, reconciling all things, the created world to Himself by His death and resurrection. The message of the Gospel involves the reconciliation of the created world to Jesus Christ. God restores the whole human person not just the spiritual to the true image of Christ. Christians are called upon to work in all spheres of human life. Belief is the basis for Christian scholarship, Christian education, and work as a vocation. All of life is spiritual, living the Gospel in public, in ordinary everyday life, and the natural realm of this world is just as serious and important as that which is related to Church life. At the same time without that inward piety that comes with knowing Christ, living for Him in every square inch of life will only be an empty slogan.

There is not one set of values to be espoused by the unbelieving world and another derived from Scripture for believers. God’s Word is equally authoritative for all men. His ordinance for marriage between one man and one woman, the raising of children and their education, how we are to understand the world in which God has placed us, all these things are equally authoritative for all. We can do no other than call upon all men high and low everywhere to submit to God in all these things and above all to give up their rebellion and acknowledge Christ as King of kings and the only Saviour of men to whom they should come in repentance and faith for redemption.

Impossible as it may appear, this is indeed the future for this sin-soaked, rebellious world. The Gospel of Christ must triumph and redemption come to a fallen race and a fallen creation. It will not come about without a fierce battle right to the end and until Christ Himself shall appear, but He must triumph. This is celebrated in Psalm 110 and applied to the Lord Jesus in Hebrews 10.

“The LORD said unto my Lord, Sit thou at my right hand, until I make thine enemies thy footstool. The LORD shall send the rod of thy strength out of Zion: rule thou in the midst of thine enemies. Thy people shall be willing in the day of thy power, in the beauties of holiness from the womb of the morning: thou hast the dew of thy youth. The LORD hath sworn, and will not repent, Thou art a priest for ever after the order of Melchizedek. The Lord at thy right hand shall strike through kings in the day of his wrath. He shall judge among the heathen, he shall fill the places with the dead bodies; he shall wound the heads over many countries. He shall drink of the brook in the way: therefore shall he lift up the head.”

“But this man, after he had offered one sacrifice for sins for ever, sat down on the right hand of God; From henceforth expecting till his enemies be made his footstool.” (Hebrews 10:12-13)

All reformed theologians are convinced of the triumph of Christ’s Kingdom, not all are agreed as to when this will occur. Some believe that this will happen before Christ returns. The rest believe it will happen only when He returns in glory. Among these there are those who believe Christ’s return will usher in the eternal Kingdom and there will be no physical reign of Christ on earth. Others believe that Christ will return, the kingdoms of this world will be crushed and His own millennial reign established on their ruins. This view was held by a large number of English puritans and is the view the present writer believes is the biblical one.

A personal note

In the late sixties, my wife and I first came into contact with the reformed faith. Before this time. we had worked tirelessly and worshipped in evangelical churches and organisations. Disenchantment with the evangelistic practices and unsound doctrine of some of the institutions with which we were associated led us further into the reformed camp. In later years, we broke entirely with evangelicalism. We have tried to foster good relations with all God’s people and therefore, probably mistakenly, we have not always spoken much about our convictions. At university I found the writings of Dutch Reformed theologians extremely helpful when reading German literature and European philosophy in my studies. It was help I was not able to find elsewhere. Being fluent in German has given us access to some of their works available only in the original Dutch, albeit reading slowly and with a dictionary to hand!

Today, I make no excuse for saying I find the reformed faith closest to the teaching of God’s inspired Word. It is this context in which I understand and propagate the Gospel of Christ. Now that evangelicalism has deteriorated beyond all recognition to what it was in the first half of the 20th century, I cannot envisage any circumstances that either of us would want to return to it. My fear is that many in the evangelical world are being given a distorted even false view of the Gospel, many believing mistakenly that they are safe for eternity. This is a tragedy indeed.

David W. Norris

Door of the Castle Church, Wittenberg, Germany

Martin Luther

.jpg)

Abraham Kuyper

Herman Bavinck

Vindiciae Contra Tyrannos

John Locke

Jonathan Edwards

This article is available in booklet form free of charge for wider distribution

Please see publications page